Leadhead

variation: Leadhead Peeking Caddis Larva

Variation: For the Leadhead Peeking Caddis Larva, replace the Flexibody tag by tying in a section of green micro chenille, one end singed to a taper.

Leadhead - A bug for the deep

I prefer fishing dry flies, terrestrials and deep surface hanging emergers to any other method. I get a greater thrill out of seeing fish coming up to take my fly from the surface than I do from nymphing or any other kind of wet-fly fishing. Sadly dry-fly fishing doesn't always work. Sometimes, it is necessary to use unweighed nymphs, wet flies, flymphs or emergers to fish just under the surface in order to be successful. That will be my second preferece. The worst thing that can happen to a fanatic dry-fly fisherman, however, is when fish are lying right down on the bottom, or are feeding in deep lies. In these circumstances my leaded bugs can be well worthwhile trying. I am not a purist although I fished dries only the first 8 years after starting fly fishing. That I only used dry flies happened more because of inexperience and because I didn't realise the value of other flies that time. The patterns I will explain in this chapter are probably the most successful deep-water flies I have ever used. I actually call them bugs or bottom bouncers. Thanks to my experience I know exactly where and when I have to go down to be successful. Some people still believe that fish are not feeding or in a taking mood when they don't rise, but most of us know that it isn't true. Statistics have proved that most food will be taken below the surface. That's why nymphs, streamers, emergers and wet flies are indispensable for fishing. A few people may see some of these larger patterns as lures or jigs but it is just the manner of their which determines what they are imitating.

WHY NYMPH FISHING

During my first years as a fly fisherman, I fished only with a dry fly and it took me some years to discover the value of nymphs. When I first developed my own nymphs, I never guessed how much satisfaction and pleasure fishing with a nymph would lead to. How many people worry about a wonderful fishing trip because bad weather conditions might spoil their entire plan and dreams? I have seen many frustrated fishermen sitting down beside the river bank because of situations they couldn't handle. Even if they knew that the fish were there they became locked in the rut of their favourite and most successful fishing method. In my opinion there are still a lot of fishermen who are afraid or don't know how to experiment. Creativity, insight, initiative and knowing how to read a river avoid a lot of frustration. Fishermen who can be freed from traditional regulations, techniques and suggested patterns can be very successful in difficult circumstances or when everyone fails. Because I grew up without any fly fishing tradition and history I may see it more objectively and that's why I can accept it when fishermen are using different fishing techniques and methods. During the years I learned to value other fishermen's techniques; methods that were completely new for me or techniques which where very special. It is not wise to argue against any method before you talking intensively with the fisherman who is using it. Try to find his thoughts and ideas behind it, you never know, maybe his arguments can even widen your skills. This is why I started nymph fishing, I believed in the ideas of somebody else. The joy of nymph fishing came with the success. Catching fish in the most difficult circumstances gives me a very good feeling and stimulates my self-confidence enormously. Confidence is probably the most important key for a fly fishermen. I also think that the search for more selective and hard to catch fish is also a matter of experience and development. As I grew older I looked not only for quieter fishing places but also for a greater challenge while in the beginning of my fly fishing experience the catch was the most important. Catching fish meant I was doing right. As growing older the catch was not the most important factor any more, although I am still very happy when I hook some good fish. I prefer to catch just one real specimen above a great number of smaller fish, even if it takes me some days. I guess today I belong among those who can say I had a wonderful fishing day only the catch was poor.

During my yearly fortnight grayling trip to the Glomma river in Norway I sometimes caught only one fish above 50cm. This fish makes my entire trip. When fishing I am completely wrapped up in the beautiful scenery and wildlife. I have grown into it and only because of this attitude can I handle hopeless situations over a long period. On high water conditions or in extremely bad weather, when fish are difficult to catch, I have learned that nymphing is usually the only successful method.

THE KVENNAN SPECIAL

Around 1980, I tied only a few nymphs for fishing in Holland and to practice my tying skills, but because of the good results I had been getting with the dry fly abroad, I was seldom prompted to use them. The first time I was seriously confronted with nymph fishing happened during one of my summer holidays in the early eighties when I met some Swedish fly fishing fanatics at the Glomma river in Norway. I usually fished in the areas around Koppang, Atna and Alvdal, but the interest in new fishing grounds and fishing pressure in that region drove me further upstream. I found a nice camping place between Tynset and Os; an area more than once described as one of the best grayling waters in Europe. In less than one hour after putting up our tent I had befriended a group of fly fishermen who already fished a couple of days and knew exactly where, when and how to tackle the river. When they invited me to accompany them during their nightly trip, I didn't realise that this was the beginning of a completely new experience.

With this group, I fished one of the most beautiful beats of that area of the mighty Glomma river. After many years of fishing those beats myself they had become my favourites fishing places in Scandinavia. One of those beats I call Otter Creek and with a very good reason. Every time I have fished this stretch I have seen otters; they are good company during the lonely nights, and is just one aspect of the fantastic wildlife in this area of Norway. Lars, one of the group members, used to fish with very heavy nymphs and this especially caught my attention. He was the only one who fished below the surface, and he did so with considerable success. His nymphing methods were not very popular in his group but after I had some interesting discussions with him I was very eager to learn more about it. The killing fly Lars was using, he called the Kvennan Special. It was named after the camping place that he had stayed and fished for more than 15 years. One evening, after a bitterly cold and rainy day when the dry fly had not been nearly as successful for me as usual, Lars invited me to his caravan to exchange some fly patterns and showing each other our tying skills. I mainly tied parachutes and he gave me an excellent tying demonstration of several of his special nymphs. I regret that I did not make proper notes on that occasion because it had given me a lot of good ideas for more nymph patterns in the future.

Lars was a very good teacher and his tying techniques were simple and effective. Because of the success with the Kvennan Special I copied the pattern and after a few attempts a reasonable one left my vice. I showed my "Kvennan Nymph" to Lars who was very complimentary. Together we went fishing and tried our just tied patterns. Lars taught me how to use this heavily weighted nymph and I showed him how to deal with parachutes. I learned some new casting techniques to cast those heavy nymphs properly and precisely. I also learned how nymphs behave in the strongly deviated bottom currents of a rapid, a very important factor that surely is very underrated by most fishermen. Lars also showed me his nymph patterns as imitations of the insects we found on the bottom. I am sure his help instilled confidence in me and was probably an instrumental influence on my subsurface fishing techniques and in the developing for the nymphs I tie today. The Kvennan Special I still remember as one of my early favourites but more importantly, it is also the model that gave me the idea for a unique set of nymphs and bugs that I devised myself. It was undoubtedly a similar situation as with the Rackelhanen.

IMPROVEMENTS

I first tied my own weighted nymphs during the winter after I had been introduced to the Kvennan Special. I was using layers of leadwire to weight them and I had a high priority to make a well-shaped underbody. The materials Lars used for his nymph were not available in Holland, but I found some satisfaction in using rabbit fur and partridge feathers. My first nymph I called Lars's Grayling Bug and it did very well. There were many modifications and changes made to the original dressings before I arrived at the patterns I use today. In a year of experiments I tried to bring some more improvements to the fly: I left out the tail and moved the body hackle much closer to the hookbend. A smaller tag in the same colour as the original pattern still existed, but it was not long before I did some colour experiments with the tag and tail too. In those days I was just beginning to recognise several species of upwinged flies but my knowledge about the insect life under the surface film was still very poor. Although I collected some larvae and examined them with great interest, most of my bugs were nothing more than the result of some creative tying experiments. When I used my variation with a long tail made from a partridge tail feather I woke up. This happened at one of my favourite fishing places, after I had inexplicable success with it. After my lessons learned from Lars I found several cased caddis larvea with long, fine extended pine-needles in front of the case. I found them not only in the river but also in the stomach of trout and grayling. One particular trout had even 8 of those huge cases in his belly. The fibres of the partridge tail feather probably gave a rather good imitation of the extended pine-needles cases I found. Beside this the fibres gave a very good action too. The imitation I saw in it was tied in reverse on the hook but this didn't bother me. Today I consider this idea to be one of the best in my developments of trout and grayling bugs.

Many people do not believe in catching grayling and trout with this long tailed fly, but I can assure you that I caught on that particular stretch of the Glomma river, more deep feeding fish than in any other season before. I called this fly 'The Lost Caddis' because for me it was a reasonable imitation of the pine-needle caddis larva released from stones or weeds. I still use this imitation today for that stretch of the river and with considerable success. Later I used a partridge body feather to shorten the tail and imitate the cased caddis without the long pine-needles in front. Now the fibres could imitate the legs and the green tag could be seen as a kind of head that peeps out.

I used to tie all the bugs using leadwire to weight them, but the split-shot that I have used since 1984 was the accidental result of having run out of leadwire on one occasion, when my only option was to place a leadshot on the hookshank just behind the eye. The "Leadheaded Grayling Bug No 1" was born. With this first leadshot bug, I fished during the winter and first part of the new season with great results, but when I tried to use the fly in the shallower waters of Central Europe, the fly became stuck in the weeds, or on the bottom or between stones. Then I had a marvellous idea, an idea that certainly had come up in the minds of several other fishermen too, especially when they liked to present their flies deep and close to the bottom. I tied an upside-down variation which I achieved by replacing the leadshot on a piece of monofilament just above the eye. This improved version of the leadheaded bug I named "The leadheaded Grayling Bug No 2", now better known as "the Leadhead". This pattern had even more action than earlier designs.

The Leadhead seems to be the pattern for trout and grayling feeding in deep inaccessible lies, places in a river where large fish feel secure. I like spots that look at first sight unfishable. It makes fly fishing more interesting and challenging. Just catching one very good fish out of such difficult pool makes my day.

After 1984 the patterns did not change much until 1990. I did some experiments with other dubbings, but I always came back to rabbit or squirrel fur. For the tag material I tried many different materials, but the fluorescent green Flexibody has given the most spectacular results and seems to be the best by far. In 1990 I made some very good variations on the Lost Caddis for shallower water. Those patterns appeared to be very effective for trout during night fishing in Scandinavia.

The latest improvement of the Leadhead was made a couple of years ago by Oliver Edwards. He is undoubtedly one of the best fly tiers of fishable realistic flies I know. In the first instance Oliver was a little sceptical when he saw my bugs, but after he fished the Leadhead he was impressed. After some discussions with me and with his view and background knowledge about insectlife, he designed his own and more realistic variation of the Leadhead, which he called the "Peeping Caddis". With superb drawings he describes his tying method in his magnificent book; "Fly Tyers Masterclass"

Although the technique to secure the leadshot on the hookshank with a piece of monofilament was just the result of a spontaneous and bright idea, I discovered recently that the German fly fisherman and fly tier Ingo Karwath developed a similar kind of nymph using exactly the same method. However his dressing is much different, it is still striking to see how two different people came to the same technique. Ingo got the inspiration for his Cousteau Nymph after reading an article by Art Lee. So Art is probably the third person who had the same idea and I am sure there were many more. Therefore it is very foolish for fly tiers to claim all the credit for themselves. So fly tiers who torment their brains just trying to develop a totally new pattern or technique will be very disappointed when they discover a similar pattern that already had been developed many years ago. To design a completely new fly or technique today seems almost impossible. Some people say that it is very difficult to design a fly that has not been tied before. I agree, because with so many fly tiers all over the world there will be hundreds of patterns that are looking very similar without people knowing it from each other. A very good example you will find in John Roberts' excellent book 'The World Best Trout Flies' where many fly fishermen from different continents or countries seem to use very similar patterns in their personal collection.

Tying sequence

(step by step photos: Leon Links)

- Put your hook into your vice and catch on the sewing-cotton. I use

sewing-cotton because I have to make a lot of windings in this stage.

Sewing-cotton is very cheap and it spares my tying thread.

- Take about a 10

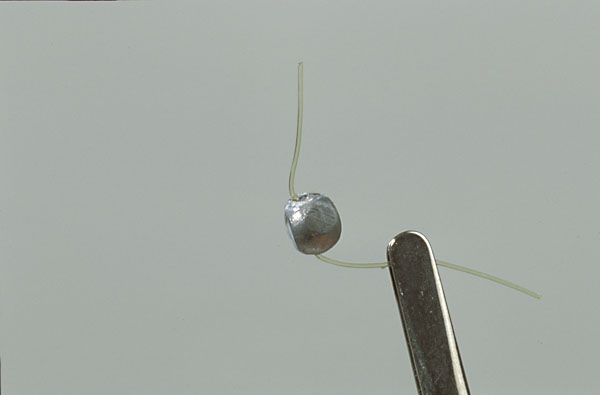

centimetre long piece of 0.30 to 0.35 mm (0.12" to 0.14") monofilament. Crimp the lead shot onto the middle of the monofilament.

- Hold the lead shot onto the top of the shank, just behind the eye with the

split facing down. This is essential for the most durable construction. Make

several windings to secure the first part of the monofilament. To avoid rotation from the lead shot a small drop of waterproof superglue on those windings can be helpful. Wind a proper underbody just after the lead shot.

- Pull the other end of the monofilament over the lead shot and secure with several wraps of tying thread. The split must be facing to the hook eye and the monofilament most be exactly on top of the lead shot.

- Cut off the ends of monofilament and varnish the underbody well.

I usually make first a large quantity of these bare leadheads before I start with proper fly tying.

- Tie in a small strip of fluorescent green Flexibody with the coloured part pointed downwards.

- Make 4 or 5 tight overlapping turns with the Flexibody, then tie off and cut off the waste.

- Tie in the partridge feather where you tied off the Flexibody. I like quite a lot of hackle fibres at the 'tail-part' (remember the pattern is tied in reverse on the hookshank) of my leadhead but if you want to imitate the legs more closely it is wise to strip away the hackle

fibres at one side before you tie in the partridge hackle.

Note: While the partridge feather could also be tied in at the tip, tying in by the butt is not only easier to wind but also produces better looking flies.

- Make 3 or 4 windings, each winding closer to the hook eye, and tie off. Cut the waste and make some extra turnings to be sure that all hackle fibres pointed backwards. Form a dubbing loop and load the dubbing into it. Twist or spin into a tight rope.

- Wind on the dubbing, secure and whip finish. The dubbing is then well picked out with a dubbing teaser.

- The leadheaded grayling bug ready for use.

Because of the weight of the fly it can be very hard to make a good, well-placed cast, especially in the beginning. Therefore a rod with a stiff or tip action is necessary in the beginning. Reduce the casting speed and watch your head.

To fish these heavy bugs the following techniques can be employed:

Dead Drifting: With this technique, I cast upstream or up and across and let the fly drift downstream as naturally as possible. My eye sight is not good so I generally use a small bite indicator, made of plastic foam, attached to the leader.

Looping the line: This second technique amazed some of my friends, because I use it exclusively on fast waters. I cast down stream, just mend the line and bring the fly back to me by looping in line with my left hand (the non casting hand). On waters with slower current this can be easily achieved with a figure-of-eight retrieve. I have found that it is very important to vary the speed of retrieving in order to succeed.

Lift-sink-lift: This technique involves an upstream cast, whereafter I let the nymph sink. When I think it has sunk enough (i.e. to the bottom) I lift the fly briefly with the rod tip and let it sink again. This sequence is repeated several times as the cast is fished out.

Stillwater motion: When fishing in stillwater I uses the rod top extensively to give the fly motion: a little movement of the rod top is combined with slow draws on the line with my non casting hand.

Sink-tip techniques: I only use sink-tip lines for extremely deep water or when rivers hold very high water. In very deep pools I take some time to get the bug down. Then I start retrieving the line with 10cm long pulls and a strongly vibrating rod tip. On rivers where the water level is very high I cast across, mend the line upstream and let it float downwards close to the bank. During the drift the fly and line will get down close to the bottom. I fish the Leadhead upstream with short pulls and a vibrating rod tip. This method allows it to fish even under deep hollow banks.

CONCLUSION

The Leadhead, originally designed for the large, deep and swift rivers of Scandinavia, has since proven ..... in many other rivers too. Over the years many anglers have fished with one of my Leaded Grayling Bugs and all have been very enthusiastic or even amazed at the results they achieved with it. That's probably the reason that so many copies of this fly exist. In still waters or reservoirs all those bugs, even fluorescent variations, do extremely well when tied slightly larger than the river version. I also caught a great number of sea-trout and grilse under the most difficult circumstances and at times when all other flies failed. In 1995 during the big floods in Norway, my Leadhead was the only fly to succeed.